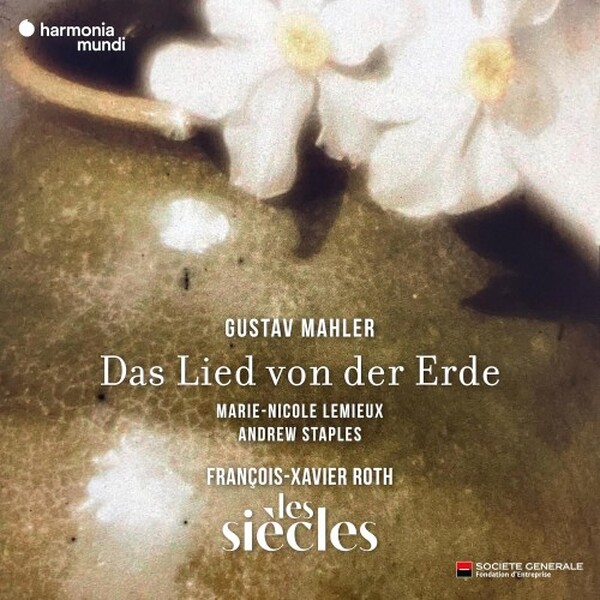

The Europadisc Review

Mahler - Das Lied von der Erde

Francois-Xavier Roth, Marie-Nicole Lemieux (contralto), Andrew Staples (tenor), Les...

£13.75

By combining so thoroughly the two strands of song and symphony that form the backbone of Mahler’s output, Das Lied von der Erde has a strong claim to be the composer’s crowning masterpiece. Its atmosphere – a mixture of joy in the world’s delights, search for self-knowledge and leave-taking – reflects the professional and personal blows that Mahler experienced in the summer of 1907, including the loss of his eldest daughter and his diagnosis with a congenital heart defect which would kill him just four years later at the age of 50. Feeling the... read more

By combining so thoroughly the two strands of song and symphony that form the backbone of Mahler’s output, Das Lied von der Erde has a strong claim to be the composer’s crowning masterpiece. Its atmos... read more

Mahler - Das Lied von der Erde

Francois-Xavier Roth, Marie-Nicole Lemieux (contralto), Andrew Staples (tenor), Les Siecles

The Spin Doctor Europadisc's Weekly Column

Celebrating Lully’s ‘Atys’ 28th January 2026

28th January 2026

It is 350 years ago this month since the premiere of Jean-Baptiste Lully’s tragédie en musique, Atys. It was performed at the court of the Sun King, Louis XIV, in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, on the western outskirts of Paris, on 10 January 1676. Its public premiere took place three months later at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal in Paris. Although its public reception was relatively muted, Atys soon became known as ‘the King’s opera’ because of Louis’s enthusiasm for it. Coming during a lull in the ongoing Franco-Dutch War of the 1670s, the opera included a lavish Prologue, populated by allegorical figures including Time, Flora and Melpomene, which heaped sycophantic praise on the monarch. The ensuing five-act tragedy, to a libretto prepared by Lully’s regular collaborator Philippe Quinault, is based on an episode from Book IV of Ovid’s Fasti. It tells the story of Attis, secretly in... read more

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £35!

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £35!